The questions I get most from visual journaling students surround the issue of the use of space on a page or spread.

There are a lot of factors that feed the questions, swirl around in the mind and stopping action.

I like to remind students that the more they journal the more these questions will find answers specific to them as artists.

Many of these questions come with a questioner’s sense that there must be a right way to approach a page.

I’ve written and taught a lot about page layout, design, but today I just want to point out to any visual journal keepers that there are 10,000 (million, gazillion) ways to handle the page. It always helps to start from the position of what appeals to YOU. It is your journal after all.

Don’t let your thoughts about the “right” way to use a page stop you from filling that page.

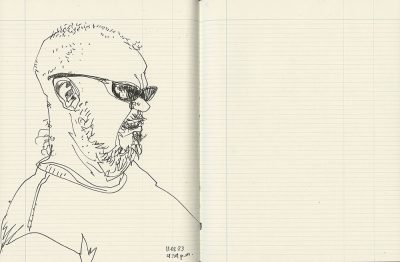

When I sit down to journal, even if the impulse begins as a sketch, I’m always thinking about where I’ll write something on the page, if I decide to write something. I’m already at the start of a page and a sketch, alright about not writing anything because I’ve journaled for so many decades and been interrupted in the middle of some grand plan because life is moving on so many times, that I know it doesn’t matter in the larger scheme of things. The thing that matters is to be present and observe and get down what I can. And to push my learning and understanding forward.

You’ve heard me talk and read my writing about the placement of the focal point based on the rule of thirds (and that rule can be applied to a single page or the whole spread).

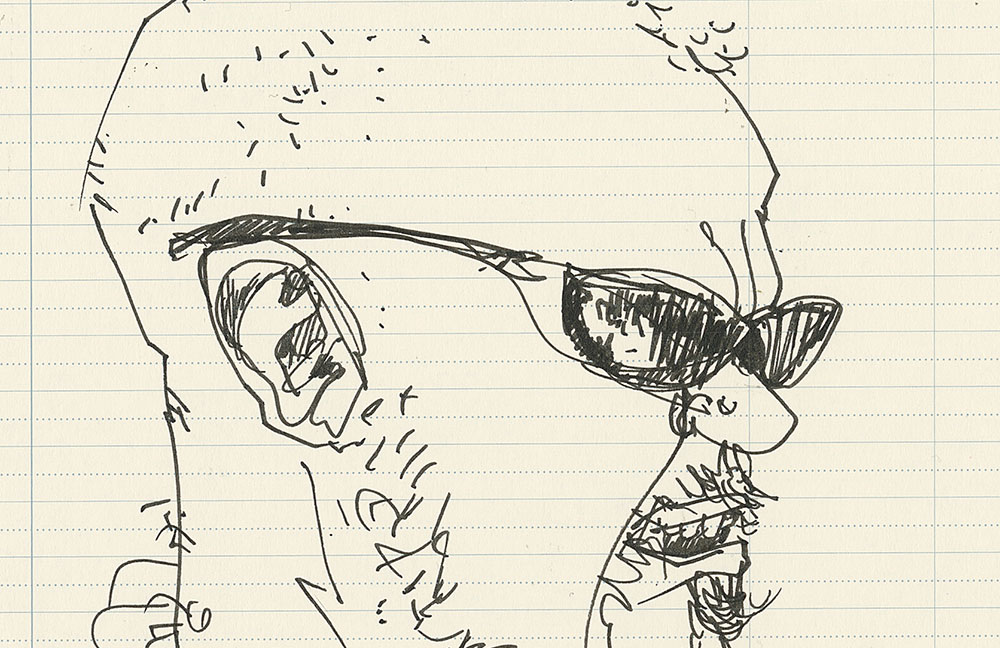

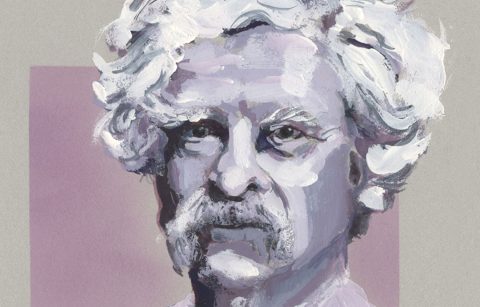

But visual journaling for me is also about negative space—those spaces around the main subject, in this instance the man on the page spread.

Recently I’ve had questions from artists wrapped up in the issue of whether or not it was a waste of paper to work only on one side of a page. The expressed concerns aren’t simply about physical realities like whether another page will show through or materials will bleed through.

The questions are about waste.

For me there is nothing wasteful about breath around a subject. It’s that breathing space on the page which invites us in to the image, helps hold us there investigating, and eventually, should we decide to include some, leads us out to the text.

If I worked only on one side of a page there would be a blank page in every spread, and then putting a man on the left, looking right, at the scale I wanted, wouldn’t be possible. The journal is for me to increase my “possibles.” It’s why I select a size and orientation of journal that gives me the options I know I crave most.

I encourage you not to think of pages left blank for any reason as “waste.”

I believe this is your internal critic trying to get you to buy into the idea of scarcity.

I know many of you might not be up to filling an entire book of your favorite discontinued watercolor paper with writing only, but I want to tell you from the other side of that repeated action there is no regret. I used what I had on hand and enjoyed the paper for all its welcoming texture and surface.

If I had stopped to consider if it were a waste to simply write on that paper I wouldn’t have written at all in those journals. Iwould have missed some of the biggest epiphanies of my life.

We select a journal that is going to enable us to do what it is we want to do on paper. And then on any given day we might be diverted from our initial path or goal, but we still have paper and we can still respond to our lives.

The first thought is always to be struck by a moment and want to get something down.

The second thought is always how to arrange something on paper.

Sometimes we make that second thought by default, jumping in and responding to live chickens in the pen before us, moving too fast for us to make the design decisions we’d hoped to make. But we always make decisions. And even those made by default help us learn about our design sense.

By all means make decisions about whether or not you want to work on both sides of a journal page because of the bleed through, show through, or even warping (from wet media on one side of the page) which doesn’t let you work the way you want to work on the other side of a page. Make those decisions consciously with an idea of the size of the page and how its scale and orientation will limit or enhance your composition.

Make those decisions with the seriousness you believe they deserve, but don’t let them interfere with more serious decision to respond to what is in front of you, and to be experimenting and learning.

One day maybe 10 years from now, or 20 years from now, you’ll look at a page where you made a design decision about use of negative space. You’ll see that it didn’t come to fruition for whatever reason. The joy of getting down what you got down on the page will vastly outweigh any concern you might have had about wasting paper.

And if you feel a twinge of regret for how you arranged something on a page take that as a signal from your editing eye that it’s time to learn something about page layout and composition, so you have have more tools to play with effortlessly. The editing eye will never talk to you of scarcity and waste, he will always encourage you to use more paper, not less, and to recast the thought of waste of paper into an understanding of the multiplying of ideas, concepts, and approaches that is full-core creativity.

Listen to the voice the points you forward.