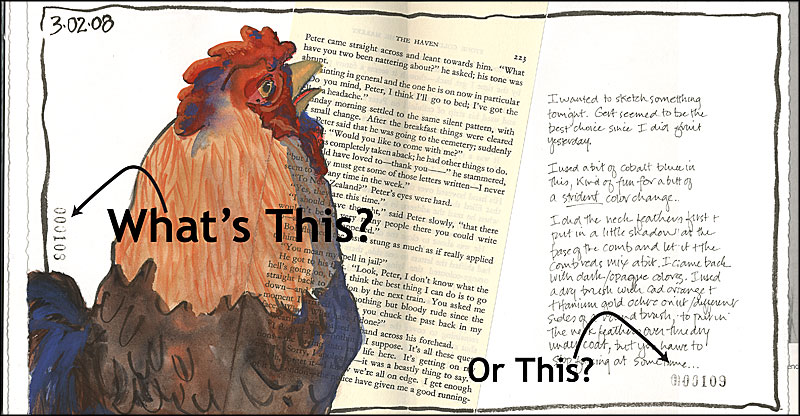

People often ask me what the black stamped numbers are on my journal pages. Those are page numbers I use for indexing. If a journal page doesn’t have a page number it means I scanned it before I finished the journal that contains it. I don’t page until I finish a journal.

I index my journals for a host of reasons. I’m compulsive, perhaps even obsessive; I like organization; but most of all I like to be able to find things again, even if I never have to find them again. I put this tendency down to a childhood spent traveling; a childhood filled with daily reminders of the importance of laying your hand on something quickly.

For decades I indexed my journals by hand. There was a list of important entries at the end of every volume: a table of contents more than an index. It was never a very satisfying solution. Things, important things, were always slipping through the cracks. My memory, which was good, but not perfect, accepted that somethings would simply be lost, or found only with a lot of page turning.

In the 1990s I started indexing digitally using a table format of key words in a wordprocessing program. That worked a lot better. I wondered why I hadn’t done this earlier. There were still more glitches than I cared for and searching digitally wasn’t totally streamlined.

In 2001 my friend Tom helped me set up a template in FileMakerPro for indexing. I changed how I numbered and organized each year’s journal volumes. Then we set up a searchable database which works with that organization. I could tweak it more, but my goal is to fill pages, not spend time cataloging.

The Process

The first journal of every year is Volume A. (In a typical year I get to Volume N or so.) I will work hard at the end of a year to finish a volume so I can start Volume A of the next year on New Year’s Day, but this isn’t essential to me. I like to think that makes me less obsessive. (Of course, I tend to be successful at starting a new volume on January 1, so the compulsive level jumps back up.)

The first page of Volume A is page 1. I page consecutively through the volume once it is filled. I use an automatic numbering machine. (I like stamped numbers.) The page numbering of Volume B starts where A leaves off. I always leave the first recto page of a journal for a title page. Page numbering always follows conventional pagination with odd numbers on the recto page, even numbers on the verso.

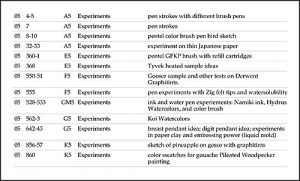

When a journal is completed and the page numbers are added I sit down at the computer with the volume in my lap and type entries into the FileMakerPro Template. I will think of as many keywords for an entry as possible to create cross references. I’ve learned there’s no sure way I’ll remember that my keyword is “jewelry” rather than “beading” so having a reference under both increases my chances of finding an item. The process takes about 5 to 10 minutes. I print out a copy on 8.5 x 11 inch paper and put it in a 3-ring notebook to have on a shelf. At then end of the year I combine and print an index for the year. A copy of the volume’s index is reduced to fit the page and glued into the last page of the journal.

Here is a section of mixed-volume entries under the key word “Experiments.” (Columns are Year, Page, Volume, Keyword, Description.)

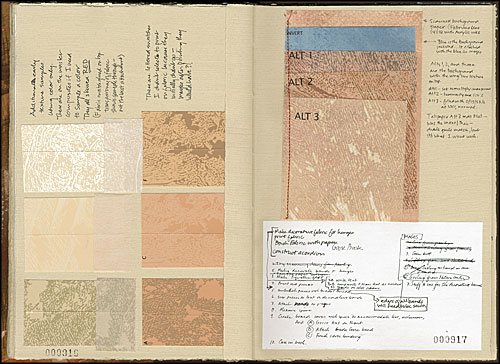

I include the volume index in the volume because the primary way I locate things is still by memory. I remember about when I drew something, wrote something, read and made notes about something, created a structure for a class. I pull that volume (all are arranged chronologically) and look at its index first. Typically my memory is helped by a memory of the type of paper I was working on at the time (I use different papers in my journals) or the fabric and decorative paper I used to cover the journal (I make my own decorative paper which is different for each volume). I find it interesting that my brain works this way; I’m grateful it still does.

If I can’t find something that way I can resort to the printed group index in the 3-ring binder, or the digital file, where I can sort my entries by year, by volume, or by keyword.

Why Would Anyone Want To Index?

For most people indexing, even a small table of contents, would be overkill. Work in your journal, move on. I actually use my journal as a research tool and filing cabinet. Through my index I can find all the raccoons, dead or alive, I’ve sketched, and use them for references or memory jogs if I need to draw one. It’s the same for anything I want to draw. I also make notes about the reading I’m doing and indexing allows me to find that information again. When I create a new bookmaking project to teach, or paint a painting, or make just about anything I keep copious notes and diagrams. My journals are filled with color swatches and step by step photos. This material allows me to make handouts quickly, or to repeat a technique without rethinking it. (I like to save time.)

Here is a page of custom printed fabric swatches I made for my artist’s book: A Gaggle.

All of that type of project material or research used to be filed in several filing cabinets in the studio. After a car accident in the 1990s I realized I’d been filing things in idiosyncratic ways. Retrieval of some items has still not been achieved. Before I would work in my journal, photocopy the pages and file them. Suddenly filing cabinets didn’t work at all, and just in time a digital organization of the journals emerged—that first wordprocessed table.

I keep the previous 10 years of journals in my studio on a series of shelves. With the exception of some painting ideas which I might revisit and finally feel I can accomplish, anything older than 5 years doesn’t get looked at much at all; but I do like knowing it’s there. Journals older than 10 years get stored in a less accessible room and boxes.

Advice for People Who Start to Index

If you do decide you want to index your journals I have a couple suggestions for you.

Look at the way you journal and the amount of pages you generate. I letter the volumes in a year because it helps me locate a volume quickly on the shelf: N7 is volume N from 2007. Before indexing digitally a date span was all I put on a journal cover. There are many other approaches that would work.

Consider pagination issues. I page continuously from the start of the year to the end because I go through a bunch of books. If I paged each volume from 1 to the end, say 100, then I would have 15 groups of 100 and if I looked on my index and saw page 10 I wouldn’t know which volume’s page 10 that was. Continuous page numbering helps me know where in the calendar year, roughly, the item fell. For some people simply dating a page spread might provide a system of pagination. (Note: I date and time all my pages important for a host of reasons not covered in this post; but clearly compulsive and obsessive.)

Specialty journals? Ask how you will handle travel journals or other special topic or theme journals in your continuous stream of indexing.

Create a system that is easy to maintain. It literally takes only 5 to 10 minutes at the completion of a journal for me to index it and move on. If something takes longer than that chances are you won’t do it consistently and inconsistent records are the most frustrating!

Once you create a system talk it over with a friend. Yes, they will roll their eyes at you and say you are being obsessive. Then they will tell you what they don’t understand about your system, or ask you what you are going to do when “Y” occurs (whatever that maybe). It definitely is worth having another mind look over your system before you put time into it and build in fatal errors. Your friend might even have a simplifying suggestion (like why don’t you abandon this course and have a piece of pie?).

Do NOT go back and index past journals. What is past is past and whatever organizational system you used will have to suffice. If you try to go back and index past journals (even if you are new to journaling and have only a few volumes to index) you’ll become bogged down in the cataloging of your past instead of being involved in the observation of your present. That is never a happy exchange.

Indexing should give you more time (by helping you find things you need more quickly), not steal your time from your work.

Alternatives to Indexing

Since indexing by hand (before the computer) was never very satisfactory, I employed additional methods of calling attention to “important” entries beyond the handwritten list at the back of a journal. When post-it notes were available I would use them at the head or fore edge of a book page. I would let the small post-its jut out like tabs, and write something on the tab so that I knew what page was marked. Before post-it notes (and yes, there was life before post-it notes) I would use a variety of office supplies, my favorite being some stiffened fabric tabs, gummed so that they would adhere to the pages. My journals from this period of time look like hedgehogs with tabs and then post-it notes (in all colors) jutting out everywhere. Sadly the gummed adhesive has a tendency to release with age and sometimes these items simply fall off the page when a book is opened now. Alternately post-it notes (even brand-name ones) can permanently adhere to a page, damaging that page.

There are a lot of ways to make journal pages retrievable. If it matters to you, you will find one that is uniquely yours, which suits your way of working, your way of thinking. I hope this explanation of how and why I index my journals helps you think about the issue.

Some of you will never bother with any of this. If you do I hope you find a way to reference your journal which reflects the uses you put your journal to and your tolerance for organization. Most importantly I hope you develop a method that doesn’t impinge on your time spent journaling.

But now you know what those little black numbers at the bottom of my journal pages are.