just what the title says.

A couple weeks ago blog reader and artist Melanie Testa wrote to ask me what brushes I like using. She wondered if I used the Niji Waterbrush exclusively.

I can see why she would think that as I write about the Niji Waterbrush a lot—always in the context of journaling out in the field. Ninety percent of the time when I paint outside the studio, either in nature or in an urban setting, I use the Niji Waterbrush as it is simple to carry and even I can’t spill water everywhere when I’m using it.

In the studio, and the other 10 percent of the time that I’m out and about sketching, I use a variety of brushes. Some favorite brushes come and go (literally they aren’t made any more), other favorite brushes are selected for a particular task and are only one of several similar brands that would be “good enough” for the same task.

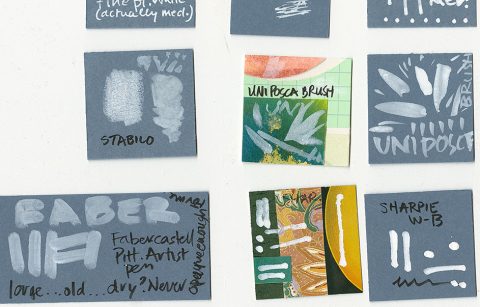

Tomorrow I will publish a group photo of some of my current workhorse brushes, with manufacturer’s information. I wanted to start the discussion about brushes first with a few thoughts on brushes. As I wrote, more and more thoughts came. Hence the need to split this post.

Some of the following points will seem commonsensical and familiar if you have used brushes (or are commonsensical), for those just starting to seek out useful brushes I hope this discussion will aid you. Keep in mind that I have a persnickety nature and sometimes I can’t help but let it kick in. When finding brushes and using brushes there is one important truism you cannot get away from: point 10. (You’ll read it when you get there.) You are the best judge of which brush is going to work for you, and the sooner you get out there and select some brushes and see what they do, the happier you’ll be. I’ve seen brilliant artists create stunning work with frayed children’s brushes. Don’t seek to acquire brushes, seek to acquire those skills.

1. Always dry your brushes flat. You don’t want them drying tip down in a container because you’ll bend their hairs, and if you dry them tip up, standing on end, you will allow water to leak down into the ferrule and this will do serious damage to your brush as it will cause the wood of the brush handle to swell and also cause the metal of the ferrule to rust. Just don’t do it if you want your brushes to stay in one piece.

2. I store my brushes in large mouthed ceramic jars of the type that kitchen supply stores sell for standing kitchen utensils (like spatulas) in (cost $5 to $10 dollars—last for ever). I also have a couple wooden cylindrical holders from Japan that were given to me as gifts (no idea on cost). Each container is LABELED as to what the brushes are used for. This isn’t because I can’t remember that watercolor brushes are for watercolor and acrylic brushes which typically have longer handles are for acrylics. I label my brush containers because I have a lot of “watercolor brushes” that are the exact same brush but use one set for watercolor and another set for gouache.

That’s the persnickety part of me, segregating water media brushes by medium. I do this because while I rinse my brushes thoroughly after I use them, there is the possibility, when working with gouache, that the more coarsely ground pigments might get caught and hide in the body of the brush, dislodging right in the middle of the most perfectly graduated WATERCOLOR wash I have ever created. I don’t want to go there.

So I have separate jars for watercolor, gouache, acrylic gouache, acrylic (which includes acrylic paints and inks), and black inks (sumi and technical inks I might use—any BLACK inks).

Depending on what I’m doing I will also use the acrylic gouache brushes for Watersoluble Colored Pencils. Though if a painting uses watercolor and watersoluble colored pencils I will use my watercolor brushes for the watercolor portions and then work with the acrylic gouache brushes for the watersoluble colored pencil bits. I tend to scrub more when working with watersoluble colored pencils and I don’t want to subject my fine quality watercolor brushes to that action and ruin their tips.

3. I am always on the look out for brush sales. While it might be nice to dream of a world where you can walk into a store and buy whatever brush you want when you want it, that isn’t realistic. My collection of brushes has grown over time based on what brush I could afford to purchase for a particular job, and what brush sales I could find. Look in art magazines for sale ads. I acquired several great Richeson brushes because they were advertised for ridiculously low, introductory set prices. Also your local art supply stores will routinely have brush sales and offer all sorts of brushes—sometimes they are “orphans” from lines no longer carried. Sometimes they are demo brushes slightly used. Other times they are…just there and inexpensive. I buy 000 and 00 brushes of all sorts of brands at these sales. It is not uncommon for me to ruin a fine detail brush in the course of a single rock painting. I’d rather toss a $2.00 brush than a $24.00 specialty brush. Look through the brushes on sale with an eye to trying new brands to see if you like the feel and spring and what they can do for you.

4. If you take care of your brushes they will work long and hard for you. I have brushes that are 30 years old and still work wonderfully well—though I have just retired my favorite sable brush because I want to keep it as a memento rather than a working tool. There’s just something about it that makes me happy, and taking it to classes and demos where it might get lost or damaged in transit just doesn’t make me happy.

5. Taking care of your brushes—that’s a huge topic and every artist working in the studio for any length of time has a range of ideas and practices and not a few superstitions, concerning the best way to take care of brushes.

I know this—keep your natural hair brushes out of any place with moths. I lived somewhere once where I didn’t realize moths were a problem and I went to open up my brush box one day (I had a lot fewer brushes then) and when I pulled out my $60 sable size 12 brush the tip stayed in the box, eaten right through! (And that’s when $60 was worth $60!) Using mothballs or other chemicals to prevent moths isn’t something I can cope with because of my reaction to chemicals. I had to move to a moth-free environment. Just keep all this in mind.

Next you’ll want to clean your brushes. I must admit that I have used special brush soaps in the past, and did so for years. Then when I actually was able to paint more, and more frequently, I stopped using the special soaps and simply rinsed my brushes. I actually think my brushes last longer with this second approach. Do what you believe works for you, but what doesn’t become burdensome and keep you from painting.

Even my acrylic brushes are simply rinsed. I do keep them suspended in water with one of those devices you see in all the catalogs—wire spring at the top over a bucket of water—you put the handle in the spring and the brush hangs tip-down into a bucket of water (mine’s ancient and no longer available). This way the tip stays wet when the brush isn’t actually in use, but the tip doesn’t push against the bottom of your water bucket. If you’re handy you can make such a device for yourself with a coil of wire (or clips), sticks, and a yogurt container. The point is you do not want the brushes you use for acrylics (paint or ink) to dry with paint or ink in them as they will then be impossible to clean.

You are on your own for oil paints as I have never used them because of allergies. Most thorough instructors or how-to-books on the subject, will walk you through the cleaning of your oil paint brushes.

6. I tend, because of the nature of acrylics (waterproof or water resistant when dry) to only use synthetic brushes with acrylics. I’m personally offended by the idea of paint being stuck in the fine hairs of my sable brushes. (That’s just me.) I also like the stiffer nature of lines like the Bristlon for acrylics, and for gouache on board or canvas board (more about this tomorrow). Synthetic brushes today have come a long way and you should not be afraid, or ashamed, of using synthetic brushes for all your painting needs. Use the brush that works for you. (If you believe in global warming—and I do—you will also immediately understand that not every sable brush is worth the price put on it. The luxurious hairs that were once used in brushes are no longer available. Texture, thickness, bounce, and volume of an animal’s coat changes over time as an animal population changes, responding to environmental factors. Again, it’s a good time to look at synthetic brushes.)

7. When a brush begins to wear out—you’ll have to define this for yourself, but the definition of a worn out brush for me is that it ceases to be good for what it was once intended. So a brush may no longer hold the fine point you depended on or you may find that the bristles are splayed every which way, etc. As long as the tip is still attached to the handle and hairs are not shedding at every stroke a brush is STILL USEFUL to me.

I rotate my worn brushes down into a new category—so worn watercolor brushes might be perfect for some aspects of gouache painting, and worn gouache brushes might be great for certain approaches in acrylic, and so on. The end of the line is a group of brushes that are so damaged and worn looking that they look as if a group of particularly mean 6-year-olds just got through with them.

Do not throw away those brushes! Those are some of the greatest brushes you’ll ever own. No matter what media you work in these brushes will make some sort of signature stroke that you can achieve no other way—but to wear a new brush down.

Brushes leave this house two ways—completely and utterly dead, i.e., the ferrule and handle break and hair goes everywhere, or the brush sheds hair all the time—believe me that’s a brush to toss immediately because nothing is as frustrating as fishing stray hairs out of a passage of any type of paint.

Worn brushes that don’t create a stroke you like can also be doctored to give you a different stroke that you might like—go ahead and give the worn brush a hair cut, jagged or smooth, tapered or flared. Then try to paint with it and see if you like it better—what have you got to lose at this point?

8. When traveling with brushes I tend to roll them up in one of those bamboo mats you see at all the supply stores, or I use a couple rubber bands to bind the brushes to a piece of cardboard that extends BEYOND the tips, and then folds over to protect the tips. (Essentially a folded card that holds them.) These are made on an as-needed-basis whenever I don’t want to carry something bulkier—most brush boxes are really bulky for my type of travel and sketching. You have to be careful with a make-shift holder though. You want to ensure that the brushes don’t slip, thereby jamming their tips into the crease of the folded cardboard. A bit of painter’s tape will hold the butt end of the handle in place along with the rubber bands. Also PLASTIC corrugated board is great for the backing of a makeshift container. Use a flat piece of PLASTIC corrugated board wide enough to space out your brushes flat on its surface. Then add a little flip cover of cardstock by attaching a piece of cardstock to the back of the plastic and flipping it over to the front. Use tape and rubber bands as usual. The beauty of the PLASTIC corrugated board is that it is waterproof and when you pack up after a session you don’t have to worry about getting your brushes out to dry as quickly. Also it’s stiffer than cardboard, while being light.

9. Don’t fear large brushes! While I use 000 (and even smaller) brushes for fine details on some paintings for most things I rely on the biggest brush possible, that will still allow me to make some detail. So I tend to work with #10 and #12 brushes the most paintings—for almost all the elements in a painting, even a painting as small as 6 x 8 inches. I can do this because I purchase brushes with good points that allow me to use them for bold and fine strokes. The advantage to this is that you also avoid the fussiness that can enter into working with smaller brushes, especially when you have to go over and over into an area. This is the best advice I can give you.

Note that brush sizes are not standard across brands so a size 4 will not be the same size from company to company, but the numbers will give you a general idea of the brush’s relative size. Many catalogs currently publish actual size photos of their brush selection so that you can avoid surprises when ordering. Going into a store where you can see the brushes in person is also helpful. Another great reason for shopping for brushes in person is that many art supply stores will furnish you with clean water and a special practice paper that responds to the water to show you the strokes you can make with that brush. This will help you determine if a brush is too limp or too stiff for your approach.

10. Give your brushes a thorough work out FREQUENTLY—it’s the only way that you will discover if a given brand is suitable for the type of work you like to do. Your preferences for paint type, thickness, and application may be so distant from mine, or any teacher you talk with, that you’ll only really know if a brush works for you after you’ve built a relationship with it.

(Tomorrow I’ll post some of my current favorite workhorse brushes.)

Wow, Roz,

What a great post. Thanks so much. Can’t wait to see your brushes tomorrow.

xoxo

Great information, Roz. Thank you!

I use a sushi roller matte too, though I have threaded two lengths of 1/4″ elastic through the bamboo slates and about 5″ away from each other. This keeps my brushes separate and just where I want them.

I use this set up full time. When brushes semi-retire they are placed at the outside of the woven matte, good favorite brushes are stored in the central portion of the matte. When brushes die, they get thrown in a drawer.

The best (non-toxic) way to clean oil brushes is to rinse them in oil to get the paint out, then wash them with brush soap to get the oil out. Make sure they’re fully dry before using again, or else the oil won’t stick well to the wet bristles.

Stacey, I don’t paint with oil paints so this isn’t something I have to worry about, but I do know my oil-painter friends are using vegetable oil or something to clean their brushes now. Thanks for weighing in.