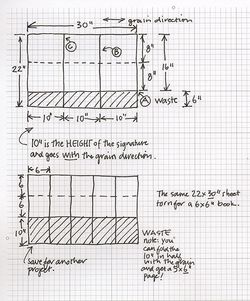

Left: A couple “fussy” tearing diagrams using a 22 x 30 inch sheet of paper with the grain going with the 30 inch side. Read below for explanations of the diagrams.

Left: A couple “fussy” tearing diagrams using a 22 x 30 inch sheet of paper with the grain going with the 30 inch side. Read below for explanations of the diagrams.

In my recent Project Friday Post I wrote about tearing paper and posted a video demonstration. I have written elsewhere from time to time on the blog about “fussy” tearing—tearing a sheet of paper down not simply by folding it in half but by first removing “waste” so that you can end up with a particular size for your final page.

Today’s post is an attempt to bring together many of those notes into one post.

You need to read my posts about finding grain direction and watch the video from Friday (all the links can be found in that post) to really understand what’s going on here if you haven’t done this before.

This post assumes that you’ve determined the grain of the full sheet of paper you are using. Also it assumes you have a particular size of book in mind for your final product.

I’m using a 22 x 30 inch sheet of paper for my disccussion. (The underlined number is my way of remembering which side the grain runs parallel with.)

In this case my hypothetical paper is Folio, but it could be any one of a number of 22 x 30 inch sheets on the market. (Remember—not all 22 x 30 inch sheets have the grain running with the 30 inch side so DETERMINE YOUR GRAIN DIRECTION before you begin planning. Also please remember that papers change over time—factories get new equipment and, well just check before you tear!)

Note: You can tear any paper in this fashion, regardless of the sheet size, as long as you can fold and tear it (i.e., it ideally should be 140 lb. weight or less). Just determine the grain direction and start working out your diagram.

In the top half of today’s image I have a diagram that shows how to tear down a 22 x 30 inch sheet for an 8 x 10 inch final page size.

I look for ways to minimize effort (i.e., number of tears) and measuring (which is repetitive).

Since I want an 8 x 10 inch book and the height of that book is the 10 inches my final fold must fall parallel with the 10 inch dimension of my final pieces (and parallel to the 30 inch side of the full sheet). You’ll see the dashed line that represents the final fold. That means I need to tear pieces that are 16 inches wide x 10 inches tall—which when folded yields a page spread of two pages, each of 8 inches in width. (You can also work out ways to do fold ups and fold downs but that’s a bit more complicated than I want to be today. I teach a whole class in that—watch for the next time it’s offered.)

Since I know the final size piece I need I have to look at how I’m going to get that out of the 22 x 30 inch sheet. The first thing I do is make sure that the height of 10 inches runs along the top of the full sheet with the grain so my fold will fall correctly with the grain. So if I have 30 inches divided by 10 that means I’m going to get THREE panels of the 10 inch height from each sheet like this. I divide my diagram into 3 panels by drawing the lines labeled B and C.

Next because I know the width needed is 16 inches I mark out that width on the 22 inch side.

Tip: Always measure out the width you WANT, not the waste. Art paper sheets come with a listed size but that is often variable by small (and important) amounts. If you were to measure the 6 inch waste strip you might not end up with a full 16 inches by the time you were through.)

I draw horizontal lines as shown in the diagram to finish off my chart. I’ll be saving this for future projects so I make sure that my notation is clear. I also list the type of paper, add the date, and make notes about the tearing sequence. All of this actually gets translated by me into an illustration in Adobe Illustrator for a database I keep, but sketches that are detailed are sufficient.

Keep your diagram handy as you tear in case you lose your way or your concentration is interrupted.

Note: I don’t use a tearing bar because I find they can slip more easily for me than the score and fold method I describe. If you are comfortable using a tearing bar do so to remove your waste strips. I would still simply fold when you get to portions that can be folded in half.

The tearing sequence for this sheet for this size of book would be as follows:

A: Measure the 16 inches from the top of the full sheet on the right and on the left. Make a small pencil mark on both edges (the mark will fall on the 22 inch sides; you are measuring from the 30 inch side down). Place a large straight edge so that it aligns with these two points along line A. With a bone folder score a line at the side of the straight edge. You should have positioned your straight edge so that the scoring takes place on the WASTE side. If you slip you ruin your waste not your main sheet. Take into account the width of the bone folder when you score and maintain this when positioning your straight edge throughout all future scorings on this project.

Note: If your full sheet has torn or deckle edges as it comes to you from the factory you will have to decide on a procedure for handling the uneven edges. I find that point in the deckle that is still “substantial and not feathery” and use that as my visual boundary line. Then I am consistent throughout that project so that I fold in a consistent manner. There isn’t a right or wrong about this, there is only the final product and whether it works for you the way you did it. I do not recommend that you try to visualize the exact edge of the sheet (minus the deckle) and use that as the point to which you meet when folding because that will result in every deckle edge of your book sticking out more at the fore edge for instance, in a very pronounced fashion. You would be better off using the most extreme edge of the deckle, where it is most feathery, as your “edge” to match up with the more uniform edge you’re folding to. You’ll end up with the heavier substatial edge jutting out more than most of the deckle and that might suit you. I don’t like that heavier edge to be too proud. But you’re going to have to tear some sheets to see what’s what; and what you like.

DO NOT LIFT THE STRAIGHT EDGE, but instead reach under the paper edge and lift the paper up against the straight edge to reinforce that line. Do not fold the paper up and over the straight edge or you’ll create a multi-edged fold. (You can see a video of me tearing paper using this method here.) When the score is clearly stated remove the straight edge and then completely fold the paper over. (It should be easy to do this now.) Keep your paper edges as even as possible at the top and bottom. With your bone folder press up and out on the crease as shown in Friday’s video. You can run the bone folder down and out one more time if you really need to restate that fold. Then insert the bone folder into the fold and tear as shown in Friday’s video.

Keep that waste paper handy, you’ll use it later. By removing the waste first we ensure that our page widths will be equal.

B: Your sheet isn’t going to be exactly 30 inches wide so you need to measure the sheet and determine what 1/3 of the sheet is and mark that measurement at line B at the top and bottom of your remaining sheet. I tend to determine 1/3 by eye, using a ruler and a measuring strip. Other people have all sorts of methods and they can help you with those.

Note: A measuring strip is a long strip of lightweight paper on which you mark your measurements so that you don’t have to keep referring to a ruler.

I measure my sheet with my ruler to see how close it really is to the stated size. I look at my ruler and work out fractions of fractions visually, and then make a mark on the paper for what I think is 1/3. I transfer this measurement to my measuring strip and then position the strip to measure the center panel, make a mark, reposition the measuring strip and see if I’ve reached the other edge of the full sheet. If I get to the third panel (I haven’t done any tearing yet I’m just working out my measuring) and something is off, I adjust the measuring strip mark to accommodate that difference (divided appropriately because I need 3 panels) and recheck until I have a measurement on my strip for 3 equal panels. Then I use that measurement strip to mark my two points on line B, positioning my measuring strip at the top and bottom of the page and measuring from the right edge of the paper in towards line B.

I then use the bone folder and straight edge as described in A above (remember not to remove the straight edge until you reinforce that fold—it is pretty impossible to put a straight edge back in place). After tearing I set that panel aside. (Save your measuring strip too.)

C: Without changing the orientation of the remaining piece of paper (because it is pretty much square now and I don’t want to tear the wrong direction) I fold IN HALF at line C. Then I simply tear as shown in the diagram. I now have three pieces to fold in half at the dotted line, and then collate into signatures.

DO NOT FOLD YOUR FIRST PANEL FROM TEAR B at this time. You may use it to measure other sheets. Using both your waste strip and your first torn page panel (or your measuring strip) you will then work with your other full sheets in this manner.

1. Place the waste panel (or your measuring strip) at the base of the next sheet and mark its height on the sheet beneath on both the left and right 22 inch sides of your paper. Remove the waste panel and score, restate, fold, and tear as explained in A above.

2. Place the first panel from the first sheet on top of the right edge of your new full sheet (from which you’ve just removed the waste) and use that first page panel to mark your height needed at line B in two places (top of the piece of paper and bottom along that line B). Score, restate, fold, and tear as explained in A above.

3. Fold and tear the remaining paper at line C, simply by folding in half as shown in Friday’s video.

4. Continue this procedure with your remaining full sheets until you have torn enough paper to make the number of signatures you want. Then fold and collate the pieces into signatures.

What to do with your waste strips of art paper.

You will have a number of waste strips if you don’t simply attack the full sheet by folding in half and in half and in half. Think about whether or not they are useful to you for binding or for flat artwork. I tend to save my elongated waste pieces to use for small sketches and thumbnails. I give some to a landscape painter friend.

If I were to use the strips from today’s first example to make a book I would have to fold the 6-inch width in half for a 3-inch wide page. That’s not very useful. But I have made some journals with such strips. (See the journal in which I drew a sketch of Dickens. It is an extreme vertical. Sometimes I tear those waste strips into smaller heights and make very small books, 3 x 4 inches or so. (These actually sell very well but I have found they are almost as much time and effort as making a full-size book so I don’t like to make these much any more. It’s useful to have a few small books like this on hand for hostest gifts and such, when a full size book would be extravagant.)

Considerations: Resist the urge to fold these strips against the grain to create pages. You will get a book that doesn’t close properly, whose pages don’t lie correctly (and have no ease), and you’ll be stressing the binding. Of course you’ll also be cracking the fibers of the paper severely everytime you open and close the book. Some papers can take this, but it is never a smart thing to do.

Considerations: If having a 6-inch strip seems useless to you, but having a 10-inch strip so that you can make a 5-inch wide book with the waste strips is something you would like, ask yourself, “Am I willing to give up the extra width on my main book’s page?” If you went for the 10-inch waste strip you would end up with a 12-inch panel that folds to 6 inches x 10 inches. Is a 6 x 10 inch page something with which you can live?

How many sheets will I need to tear?

With heavyweight art paper such as 140 lb. watercolor paper, or this heavy weight printmaking paper in today’s example, I like to have only 4 pieces of paper in each signature. When folded and collated they create a 16-page signature.

You’ll need to make a decision about how thick you want your signatures both in actual thickness and in the number of pages they contain. In today’s example that’s the signature size in pages for which I’m aiming.

Let’s also say I want a 4-signature book. That means I have to tear down 6 pieces of this paper to get 18 panels. When I divide them into signatures of 4 pieces each I am left with two pieces. So I can make a 4-signature book with 6 full sheets of this paper.

If I don’t want to have any paper left over I can tear down 12 full sheets and end up with 9 signatures (each with four pieces in them). I could then make one 4-signature book and one 5-signature book, or one really thick 9-signature book.

I tend to make books for journaling that have between 4 to 12 signatures. It depends on the paper type and intent for the book. If I’m going to the State Fair I might want the maximum number of pages possible, but use thinner paper to keep the bulk of the spine and the weight of the book down.

You get the idea.

When I make a book all the signatures are the same thickness. I do this for balance and for sewing considerations (tension). Experiment as you feel comfortable. I don’t see the point of trying to fit two extra pieces of paper in a book, because typically I tear down enough full sheets that there are sufficent pieces to divide equally by 4.

Example Two in the diagram above

The second portion of the diagram above shows a tear diagram for a 6 x 6 inch book. Again your final fold has to run with the 30-inch side of the paper (see the dashed line). To get a 6-inch wide book you need your pieces to be 12 inches wide. That means you’ll have 10 inches of waste. (Measure 12 inches to take off your 10, remember—measure what you want not the waste!). Now you have a waste piece that actually might be useful. A straight, non-fussy tear on that strip could yield 4 pieces that are 5 x 7-1/2 inches when folded, or you could tear it to the 6 inch height.

When tearing the height I recommend you again determine what the measurement of each panel will actually be (slightly less, more, or exactly 6 inches depending on your sheet’s real measurement) and then starting at one side measure for ONE panel. Follow instructions about how to use a measuring strip, and how to score, fold, and tear in the first example above.

What you are left with after removal of one panel is a piece that you can simply fold in half once and tear, and then fold each of those two pieces in half and tear. (Keep the grain direction in the proper orientation—you must tear against the grain in these final tears so that your final fold will be with the grain.)

My basic approach is to get as quickly as possible to tears that you don’t have to measure—but simply have to fold in half to achieve. (Again, see the video from Friday for instructions on how to fold and tear in this fashion.)

Get it? Got it? Good. Now tear.

The examples I’ve gone over today are just two of an infinite number of possibilities. You need to look at your full sheet, its grain direction, and your own desire for books of a certain dimension and then impose those constraints onto your full sheet. The math involved is pretty minimal; the rewards are phenomenal.

You get to have a book that contains the paper you want to use, in the size and format with which you want to work. If you have a particular bag or pack where space is tight and no commercial journal will fit, you can create books that work. If you are like me and need to keep what you carry to a minimum then you’ll be able to skate right to the edge of what you can carry by adjusting your book sizes accordingly. And again, if you are like me and really like square books…enough said. Go make a book.

Update 2.28.12—I just remembered that I wrote about how to select a size of book that works for you (so that you can then make books that size) in “Choosing a Journal Size.” If you would like to read a discussion of the process from my point of view please check that post out too.

Roz, you know I’ve taken several bookmaking classes with you, but I found this post so helpful. I need these reminders. Thank you so much for all of the time and effort you put into sharing all of this.

-Briana

Great post, Roz, and so valuable.

Do you have any hints or advice on tearing the untraditional sized papers. I have three here, all different sizes, and all under 22×30 that I want to bind in an experimental attempt to re-entering bookbinding.

Zoe, I tear all papers like this. I’m assuming here that you mean “untraditional sized papers” to mean those that are not in standard sizes like 22 x 30, instead of papers that are covered with some kind of unusual sizing.

The only thing you have to do is decide grain direction (follow my links from Friday’s post to a post on how to do that) and measure the sheet and mark up a diagram just as I’ve shown here in this post.

So if you had a 12 x 16 inch sheet and the grain ran with the 16 inch side you could fit two 8 inch heights along the 16 inch grain direction and have a 6 x 8 inch book without any waste, easy peasy. (Because the 12 inch width would fold in half to make 6 inch wide pages.

If the grain direction went with the 12 inch side of the paper you’d have an 8 inch width and could have a 6 inch height for a landscape book.

If by untraditional (and I think nontraditional would be a better description) you’re asking about HANDMADE papers, then you’re in luck, because there isn’t a pronounced grain with handmade papers because the fibers don’t come down the line as it were, but are scooped up into the screen out of the vat and slosh around in the screen until they are set down.

When working with handmade papers (which I almost never do) you’re probably best asking the maker of the paper, because Twin Rocker is handmade but I seem to remember that there was a definite grain direction with that paper.

I have added a note to the main post about this because I assumed I was clear that the 22 x 30 inch sheet was just a hypothetical.

Hope that helps. Thanks for helping me clear up this potential confusion for others.

Thank you very much, Roz. I meant different sizes but I also have hand made paper so your answer is going to help with both.

I have the paper out and the fixings, now I have do some measuring and marking.

Great Zoe, I hope you had a fun time working out how to use your papers for a customized handmade book! Have fun using the book.

This was so helpful, and so easy! I had not realized I could tear heavy paper like this with my bone folder, and I love the edges that result. Much better than cutting. Thank you so much.

Elizabeth, I’m assuming you watched the video I posted in the previous post as well as read this. Hope so, it will make it even easier.

Glad this method worked for you and that you can happily tear all your papers now! (I love the edge too!)

You bet I watched the video! I am a big believer in that saying popularized by This Old House–Measure Twice, Cut Once. For me that includes watching instructions to be absolutely sure I know what I am doing before I actually do it and then wonder what the heck I was trying to accomplish.

Just a follow-up note: I found that the waste strips from each paper (I used the first diagram, removing a six-inch strip in order to end up with pages 8×10″ in the final result) were perfect to add in to my signatures as stubs/foreshortened pages. Since I am going to use this as a travel journal, I knew I needed plenty of extra space at my spine to allow for all the paper I gather to add in during our trip (and we are going to the Olympics–!!!–so I expect to collect plenty of stuff).

I folded some equally so they were 3×3″, some off-center so I got a “page” about 1-1/2″ wide and the other then about 4-1/2″, and some I tore in half (with the grain) and then folded with the grain again, so that each stub was 1-1/2″. Just thought I’d mention it as another option for using the “waste” strip.

Elizabeth, I didn’t find your comment until today, months later. Sorry. I hope you had a great trip. I wanted to point something out to you for future reference.

If you look at my post on making a journal with scraps http://typepad.rozwoundup.com/roz_wound_up/2012/03/project-friday-making-a-journal-out-of-paper-scraps.html

you’ll see I make a different type of book construction. I sew on the spine. I bring this up because if you are going to be adding a lot of stuff to your pages, such as collage materials collected on your trip, or photos and maps, then working with a sewn on the spine construction is ideal because you can add a ton of stuff and the spine can’t bust.

I find this easier than creating a casebound book with a sewn textblock in which you add stubbs throughout to make space for the future collage and protect the spine. I used to do this now and then and it is a pain (for me) to then weight the books for drying, because I have to quickly insert all sorts of loose paper from the fore edge in to the tabs, here and there in the book before I place it under weights so that it is actually flat under the weights instead of thinner at the fore edge than at the spine.

This bothers me so much in fact that I rarely make a book in this way any more (with tabs). I won’t say that I’ll never do this again, but I would have to have a really important reason and be paid a lot of money for the inconvenience.

Instead what I do, which is what I always did in commercially made books, and in all my books that I didn’t bind with tabs (which was 99.9 percent of the books I’d made) I always start a book by cutting out some pages and leaving a tab. You can see a video of me doing this here

http://typepad.rozwoundup.com/roz_wound_up/2009/05/adventures-in-bookbinding-roz-shows-you-how-to-support-glue-seams-in-a-casebound-book.html

I find that the “waste” of paper is less than my hourly cost of binding with tabs and the fiddliness of that. And the waste isn’t waste because those cut out sheets are used in other projects.

I have a bookbinding friend who solves this problem differently. She cuts and folds cardstock to the size of her folded signatures and puts these on the outside of her signature just like regular pages, sews up and constructs the book. Then when she gets to these pages she cuts the cardboard out, leaving tabs, and they create the space at the spine that will allow for additional collage material on the pages, BUT she doesn’t have do deal with any fussing over tabs in the construction of the book. I think that’s a very elegant solution you might like to try if you opt to continue in this fashion.

But I wanted to be sure to mention the sewn-on-the-spine books as they can also solve the issues you’re dealing with.

Again, I hope your trip to the Olympics was wonderful and you can try these out on future trips.